Debunking Preservation Myths

Historic properties enrich our cities and capture our history. Don’t let myths about extra costs and over-regulation outweigh the benefits of undertaking your historic project!

Historic buildings can’t be sustainable.

FALSE.

Several well-known historic buildings have been renovated to meet LEED standards. The U.S. Green Building Council recognizes historic buildings “represent significant embodied energy and cultural value”. LEED offers credits for the preservation or adaptive reuse of historic materials and features. New technologies and products make it possible to integrate sustainable solutions that improve the performance of a historic property. The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation include special Guidelines on Sustainability. Work with a historic architect to determine if any of the following modifications could improve building performance without permanently damaging historic materials:

- Windows | Restore windows by replacing putty or weather-stripping to create an air-tight window opening.

- Interior Storm Window | Installing interior storm windows can nearly double the window’s insulating value. A compression fit assembly can be installed without any additional hardware or holes in the historic frame.

- Insulation | Historic buildings may not have any insulation. Blown-In insulation products can be installed into walls through small holes or attic access to improve energy performance.

- HVAC | After testing the existing system for efficiency, a new HVAC system can be installed as necessary within the replacement cycle. High velocity air ducts have a slim profile and can be retrofit into existing walls to avoid visible ductwork or additional soffits.

- Restoration | Inherently sustainable features, like skylights and operable windows, naturally improve occupant comfort since they predate electricity.

A designated historic building can’t be altered for ADA accessibility.

FALSE.

With the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, access to properties open to the public is a civil right. This doesn’t mean every property is required to install an elevator. A property should have the highest level of accessibility while minimizing changes to the historic properties’ character, as outlined in the Preservation Brief “Making Historic Properties Accessible”. Historic architects work with you to thoughtfully integrate accessible elements to minimize permanent alterations to historic materials or characteristics. Common alterations to improve accessibility include:

- Entry | Providing accessible parking and regrading or adding ramps to enter the property

- Interior Circulation | Installing ramps, over steps or door thresholds for access to primary areas of significance within the building

- Door Openers | Retrofitting heavy historic doors with an electronic opener to ease access and improve clearance

- Restrooms | Adding grab bars, increasing restroom size, or installing restrooms in an attached or detached addition

- Elevator or Lift | In a major renovation, installing an elevator or lift to access several levels of the building

- Alternative Provisions | Audio/Visual displays to represent inaccessible areas of a property, or alterations that meet the performance intent of the accessibility code without meeting the exact dimensions and slopes

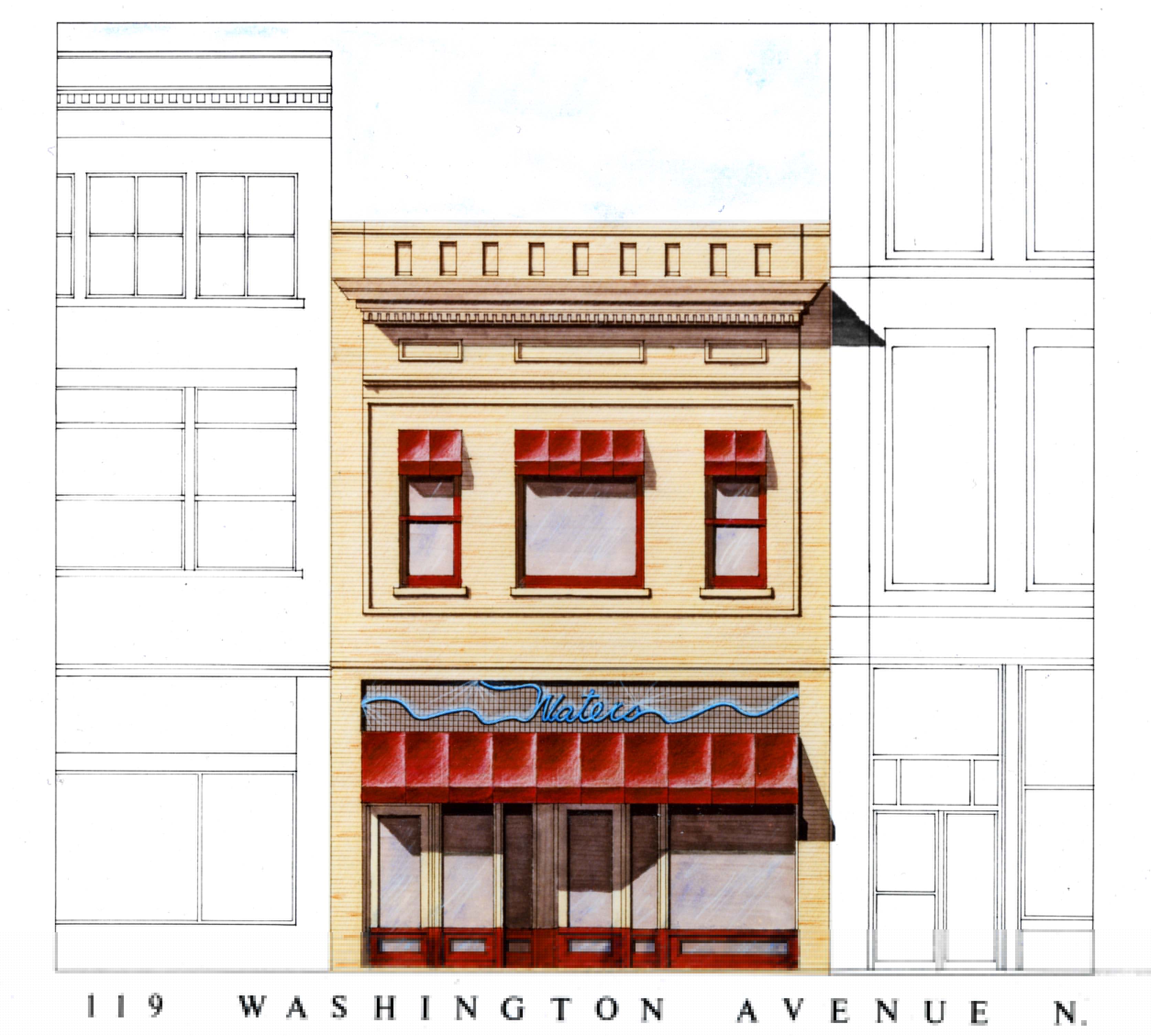

A building located in a historic district can’t be modified.

FALSE.

Historic districts include contributing, non-contributing, and potentially new structures. The district guidelines regulate but shouldn’t prevent appropriate modifications or new construction. A contributing property adds to the historical integrity and modifications, although necessary, may be regulated. For example, repainting trim and repointing brick preserve the building. However, the paint color or profile of the brick joint may need to adhere to the district’s guidelines. Non-contributing properties, including new construction, are not from the period of significance. The regulations for non-contributing structures vary, but often guidelines outline design parameters that ensure these properties don’t over-whelm or distract from the historic character of the district.

Rehabilitating a historic building is more expensive than building new.

FALSE.

Historic preservation often encounters the same project contingencies and challenges as new construction. Assessing existing conditions of a historic property helps anticipate unforeseen work items that could pause construction or increased project costs. Historic preservation or rehabilitation projects often start with a condition assessment report that investigates the entire building. The cost of this initial step can be offset by state grants. Historic architects go through the following process to set up historic projects for success:

- Investigate | identify hazardous materials, locate structural elements, and test the condition of existing materials

- Define Historic Character | identify materials and design features that significantly contribute to historic character

- Assess | analyze and predict causes of visible conditions

- Recommend | list recommendations for each material, assembly, or condition reviewed by the report

- Prioritize | define scope of work, assign priority levels to recommendations based on preservation impact or detriment

Only old buildings can be historic.

NOT NECESSARILY.

Properties gain historic significance by association with historic events, persons, or distinctive characteristics of artistry, style, or construction techniques. Historic listings recognize a properties’ significance at local, state, or national levels and each list defines its own prerequisites for selecting eligible properties. At a national level, the National Register of Historic Places (NHRP) states that “properties that have achieved significance within the past 50 years shall not be considered eligible for the National Register” unless the property is of “exceptional importance”. However, a building or district can be nominated any time they meet that special consideration of “exceptional importance”. With the speed of construction in contemporary cities, sometimes an early listing saves a historic property from demolition before it reaches the 50-year mark.